VIEWS ON VENICE

First things first: the book ‘Giuseppina della Laguna’ is out! In a limited edition of ten, it tells the story of that mysterious little girl who lives in the Venetian lagoon. You can watch the series here. This charity edition, which sells for € 275, holds five extra photos. The net proceeds (€ 225) will go towards restoring the damages caused by the horrific flooding of Venice, exactly one year ago.

If you feel a connection with this city-unlike-any-other and consider making a donation, why not do so now? A unique book, hand-printed, numbered and signed, will come your way – in sincerest gratitude. Drop us an email and we’ll sort it out.

That was the commercial break. Now back to our regular program.

THE CITY IN ART

“There was neither the symmetry nor the richness of materials I expected,” a disappointed British visitor of Venice remarked in 1774. He had seen the paintings of Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal, 1697-1768), and to his dismay he realised that the painter had been rather nonchalant about reality.

Canaletto was a star in 18th-century England. In his hometown of Venice, he had met John Smith, an English art collector, who acquired most of Canaletto’s works and sold them on to the British king, George III, in 1763. (Consequently, the municipality of Venice only owns two Canalettos, while the Royal Collection has loads, as does the Wallace Collection, also in the UK.) Canaletto was invited to London where he made many more cityscapes, aka ‘vedute’ – veduta means ‘seen’ in Italian.

Canaletto’s nonchalance is a hot topic with art historians. There’s a lot of discussion about his work method: did he use a camera obscura to accomplish his astonishing lines and perspective? Or did he make an underdrawing with pencil and rulers? The latter we know for sure, it is visible with IR-research. But why should one exclude the other? The camera obscura seems to be a bit of a touchy subject, as if it is something improper. I don’t really get that. I’m going to devote a separate post to that. But first back to the vedute and the (un)realistic representation. I for one don’t mind at all that the vedutisti took those liberties – it’s a great way to practice close-reading an image.

These two Canalettos, both from the 1820’s, clearly show the liberties he took. We see the same area, but in the image below he pasted the steps of a bridge against the building – I suspect it is the bridge ‘behind’ us, on the other side of the Doges palace. Hey, minor detail. The church with the white domes is the Santa Maria della Saluta (St Mary of Health), built after a horrific outbreak of the plague. That building with the ball on top is the Dogana, the customs office. Both feature heavily in nine out of ten vedute, and in reality they are further away from each other. But this works wonders for the composition.

Francesco Guardi is the other famous Venetian cityscape guy. Fifteen years younger than Canaletto, part of a large family of painters. This is his rendition of the Tre Archi bridge, across the Canale di Cannareggio (ca 1770). I used to cross that bridge almost daily, my apartment was pretty much next to it, and I can assure you the water isn’t nearly as wide as here in Guardi’s painting. And the bridge isn’t curved, it is straight as an arrow. It crosses the also-straight canal in a straight line.

Bernardo Bellotto, ca 1738. Canal Grande. The palazzo on the left, with the wooden pointed roof, is Ca’ Rezzonico being built (it’s much higher now). In the background you see the tower of the Basilica dei Frari, in front of it is Palazzo Balbi, nowadays home of the regional government. So far, so accurate. But the light? Totally inaccurate yet again. Is it coming from the right (the east) or from the front? He did paint it beautifully, with that stormy, sort of impressionistic sky and all those highlighted details. The boat on the right is fabulous, it has a little roof terrace!

James Holland (ca 1840) has probably done his sketches sitting on a boat. The mooring post on the right suggests he’s on land, but then that would be Giudecca and that can’t be, that’s much further away. The fact is, there are mooring posts everywhere in the middle of the lagoon, but this one certainly isn’t there anymore – they deepened the whole Canale di Giudecca to accommodate those stupid cruise ships. True to life or not, he gives us two exemplary colors of Venice – that peachy pink and the turquoise. Although the Doges palace, on the right, isn’t really peachy but more beigey. Oh well.

JMW Turner (ca 1841). Same spot, but seen from the other side. An art critic said of this painting: “Venice was surely built to be painted by Turner”. How very true. Turner added some inexplicable details here – that unit in the middle, it looks like a quotation of Saint Mark’s basilica. No idea what it is. And there in the lower righthand corner, the things in front of those teeny tiny dogs, what are those? A revolver? A giant orange? A Chinese vase?

Another Turner (1840). The lagoon at sunset. Those colors again. So beautiful, I could weep. And, at least to me, so very Venetian. The first time I flew into Venice, the sky was full of enormous pink, orange and red flames. Turner to the max. Later I would often sit at the waterside in the north-west of the city, watching the lagoon at sunset, seeing this.

John Singer Sargent, 1904. Again, those colors! Again, one of my heroes! And the same spot again, though from a totally different position this time. Apparently tourism is on the rise – it is starting to become pretty crowded near the Doges palace. On the right you see the infamous pillars of the Piazzetta (the small square on the waterfront). A Venetian will never walk in between the two. That would bring bad luck, since the spot originally was an execution site.

Singer Sargent also saw different colors of the city: ‘Venice in grey weather’, ca. 1880. Actually, those dates don’t really matter – hardly anything changes there. Check this live webcam.

James McNeill Whistler makes us turn 180 degrees. ‘Nocturne in Blue and Silver. Also from 1880. Breathtaking.

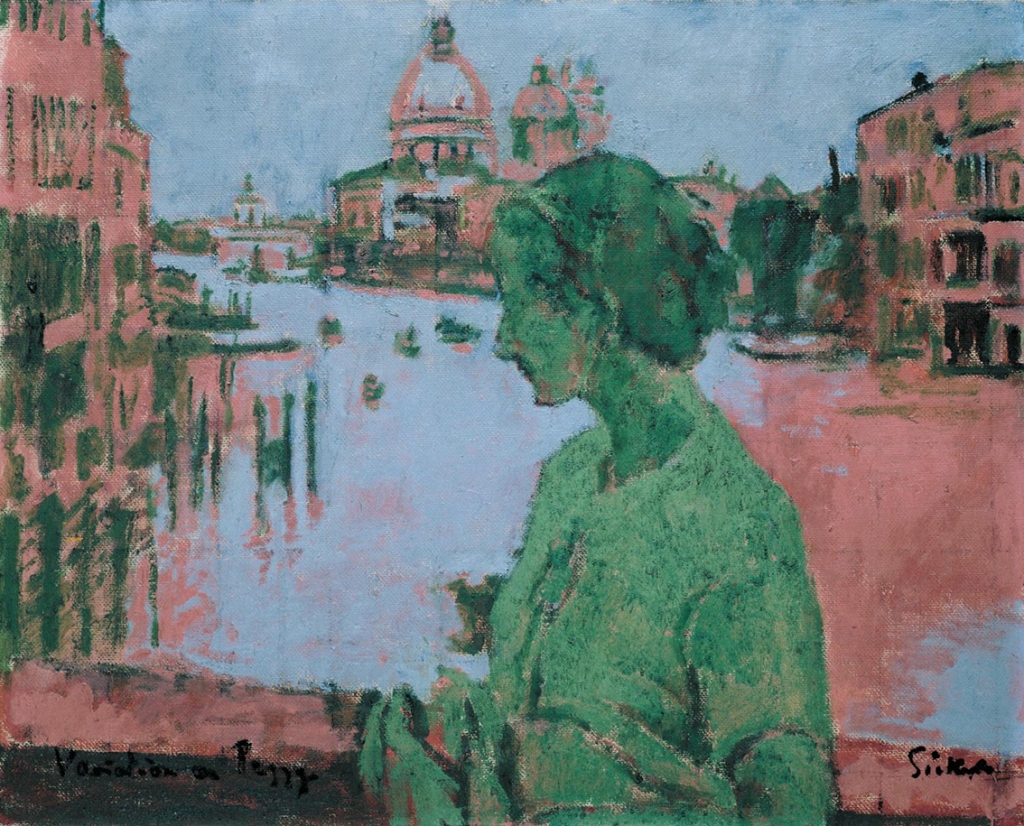

Walter Sickert, 1935. ‘Variations on Peggy’. You immediately think of Peggy Guggenheim and her famous art collection, but this refers to Peggy Ashcroft, the actress. That Sickert fellow I need to write some more about. Stunning work, rather shady character. Possibly even very shady – but you don’t notice that here, just a beautiful, intriguing image, clearly influenced by photography, and yet again, those colors . . .

To finish, back to Turner once more. This is his hommage to Canaletto, the partiarch, the supreme deity of anyone who ever depicted Venice. He’s standing there behind his easel, by the wall on the left.

Signore Canaletto, Turner, Sargent et al – grazie. Grazie mille!

l

la